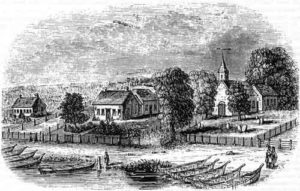

St. Peter’s

St. Peter’s was a community of Cree and Saulteaux peoples in the Red River Valley, in what is today southern Manitoba. A band of Swampy Crees, led by Chief Peguis, and Saulteaux peoples established the community as an agricultural settlement in the early nineteenth century. The missionary John Cockran set up an Anglican parish and church, called St. Peter’s, for Peguis’s band in the 1830s, and it is from here that the community got its name. Yet aside from Chief Peguis himself, Cockran received few converts, and the parish itself was only a small fraction of a much larger Cree and Saulteaux territory in the Red River Valley. Nonetheless, St. Peter’s parish and its associated mission village has often been used interchangeably to describe the larger Indigenous community along this stretch of the Red River.

The Selkirk Treaty

In 1811, the Hudson’s Bay Company “granted” a vast tract of land that it “neither owned nor controlled” to the Scottish Lord Selkirk (Burrows, 39). The area centered around the Red and Assiniboine River valley, encompassing what is today much of southern Manitoba. A few years later, in 1817, the “Selkirk Treaty” recognized the territory from Lake Winnipeg to Sugar Point on both sides of the Red River as the “Indian reserve” and as the territory of its mostly Saulteaux and Swampy Cree residents. Yet the treaty also “ceded” a 2-mile strip of riverfront land which was to be used intensively for white settlement. While white Canadians understood the treaty as a clear land sale, it is unlikely that the Cree and Saulteaux signatories understood it the same way, and more probably saw it as a sort of land sharing or tenant-use agreement, where the Cree and Saulteaux rented the narrow strip of river land to white settlers.

Treaty 1

As white settlement continued to grow in the Red River valley, and with the 1869-70 conflict over territory between Métis and the Dominion Government, the Cree and Saulteaux sought a formal treaty with the Canadian Government. The government agreed to do so in 1871. With Treaty 1 the government recognized what was then mostly Saulteaux and Swampy Cree territory in the Red River Valley as an Indian Reserve and promised to protect it from white settler encroachment. Yet soon after signing the treaty, Indian Affairs officials and other colonial agents continued to push the Indian bands and their Reserves away from the white settlements along the Red and Assiniboine River. Post-1871 surveys of Reserves further reduced the land available to the Saulteaux and Cree people.

A particularly overt transgression of Treaty 1 occurred around the area of Sugar Point, recognized in the treaty as what it in reality was: Cree and Saulteaux territory. Yet in 1875, the Canadian Pacific Railway planned to build a bridge over the Red River in the Sugar Point area, leading white settlers, in a unilateral violation of Treaty 1, to begin a settlement in the region. This illegal settlement became the Towns of East and West Selkirk.

A Fraudulent Surrender

While Treaty 1 promised agricultural aid, the government provided little in the way of tools and help, and the materials and livestock it did send were of poor quality. Nonetheless, St. Peter’s remained a thriving agricultural settlement, and its Indigenous inhabitants were cultivating over 2,000 acres of land by the late 1870s.

Despite this agricultural success, the government and white settlers accused St. Peter’s Indigenous farmers as being insufficiently productive. The government claimed white settlers could make better use of what remained of the Saulteaux and Cree’s territory, and in 1908 the Department of Indian Affairs closed the St. Peter’s Reserve. St. Peter’s residents did technically vote as to whether they would surrender their Reserve land, but the government carried out the vote in an intentionally confusing and inappropriate manner. The government gave St. Peter’s residents extremely short notice about the vote and consequently many were unable to attend. Furthermore, the government officials present explained the voting proceedings exclusively in English, despite many participants not speaking the language. The government used several other tactics to intentionally confuse voters, and the actual vote count itself is of dubious accuracy. For these reasons the Indian Reserve Commission declared the surrender invalid in 1911. Yet by then, like the Ojibwe at Long Sault only a few years later, the Cree and Saulteaux people of St. Peter’s had already been forced from their land by way of the bureaucratic processes of a democratic government.

Today

After the Canadian government took their land, most of the St. Peter’s inhabitants went on to establish a new reserve on the Fisher River, as the Peguis First Nation. Despite the new reserve’s remote location and poorer land quality, white settlers still claimed that Indigenous peoples were wasting valuable agricultural land and that this new reserve’s land should also be appropriated. Yet this second reserve was better able to withstand the pressure, and still exists today. In 2008 members of the Peguis First Nation accepted a land-claim settlement of $126 million to compensate for what is now recognized as the illegal land transfer of St. Peter’s Reserve. The legal settlement is one of the largest single claims of its kind in Canada.

Sources

Burrows, Paul P. “‘As She Shall Deem Just’: Treaty 1 and the Ethnic Cleansing of the St. Peter’s Reserve, 1871-1934.” Master’s Diss., University of Manitoba, 2009.

Carter, Sarah. Lost Harvests: Prairie Indian Reserve Farmers and Government Policy. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s Press, 1990.