Long Sault

Much of Du Vernet’s diary describes his visit to the Long Sault reserve. While the reserve itself was relatively new, the Long Sault as a historical site stretches back millennia. Located along the Rainy River, the area is considered a sacred site and today is called once more by its Ojibwe name, Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung, the “place of the long rapids.”

Early History

According to archaeological ways of naming epochs of time, the earliest residents of the Long Sault area are thought to be from the Archaic culture, some 8,000 to 2,000 years ago. It was the Laurel culture, however, that left behind the first ancient burial mounds. The Laurel people occupied the region from about 350 BC to 1100 AD, establishing seasonal camps to fish the Rainy River’s sturgeon. They were succeeded by the Black Duck people, who continued the practice of building burial mounds.

European Contact

In about 1688, the French became the first Europeans to visit the Rainy River valley. They found a land peopled by Assiniboine, Cree, Sioux, and Ojibwe, who contended over territory. While the Ojibwe initially had only a minor role in the conflict, in the late-eighteenth century they, together with the Cree, forced the Sioux out of the region. As the Cree later withdrew to the north, the Ojibwe became the principal inhabitants of the Rainy River valley. The Long Sault rapids area has, at least on a seasonal basis, been occupied by the Ojibwe ever since.

The Reserve System

In 1873, Ojibwe chiefs in what is now northwestern Ontario signed Treaty 3, or the Manidoo Mazina’igan (“Spirit Paper” or “Sacred Document”) The Ojibwe negotiated the Treaty as an agreement to share their land and waterways with the Crown, yet the Canadian government continually disregarded such notions. Instead, the government used the Treaty as a further pretext to take Ojibwe territory and restrict Ojibwe communities to Indian Reserves, all the while expanding white settlement in the region and enlarging large scale resource exploitation.

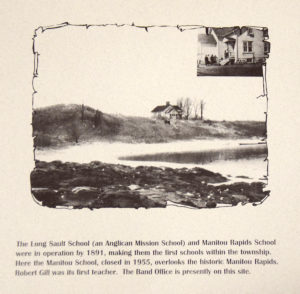

Treaty 3 created seven Indian Reserves along the Rainy River, one of which was established at Long Sault. The Long Sault reserve was one of the largest reserves on the Rainy River, forming a block of almost 11,000 acres. As at other reserves, the Treaty encouraged the Ojibwe to take up a settled, farming lifestyle, and to send their children to schools and to build churches on their land.

Christianity was not warmly welcomed at Long Sault, and it was only in 1896, with the arrival of the Anglican missionary Jeremiah Johnston, that a Church was built there. When Du Vernet arrived, a vast majority of the people that lived at Long Sault were non-Christian. Indeed, it took until 1905 for the first confirmation to occur at Long Sault, and there were only about half a dozen committed church members. Nonetheless, the Anglican Church considered the Long Sault mission a success and based its other Rainy River operations from there.

While Treaty 3 claimed to support farming among the Long Sault Ojibwe, the Federal government did more to obstruct rather than encourage this goal. By 1914, the government argued that the Ojibwe were not sufficiently productive as farmers, and consequently their land should be given to white settlers. Representatives from each reserve visited Ottawa to argue for maintaining their own separate political authority, but the government refused their requests. In 1914 and 1915, the government amalgamated Long Sault reserve with the five other reserves created by Treaty 3 into one single Manitou Rapids reserve. From 1916 to 1919, the Ojibwe were removed from Long Sault Reserves to the new reserve upriver. The land at Long Sault was bought by white settlers, who wanted to dig it up not for planting, but for gravel.

Today

Despite forcing the Ojibwe off the land, the Long Sault site was never fully occupied by white settlers. In the 1990s, the Rainy River First Nations bought back part of the Long Sault Site from the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. After a long legal battle with the Canadian and Ontario governments to reclaim their land, in 2004 the Rainy River First Nations won a $71 million land claim settlement. Today the site is home to the Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung Historical Centre, where the region’s long history is displayed. In recognition of its ancient origins, the Historic Sites and Monuments Board declared Long Sault a National Historic Site of Canada in 1969.

Sources

Animikii, Robert Horton. “A Seventh Fire Spark Preparing the Seventh Generation: What are the Education Related Needs and Concerns of Students from Rainy River First Nations?” Master’s Diss., Lakehead University, 2011.

Anishinaabe Nation Grand Council Treaty 3.