Hungry Hall

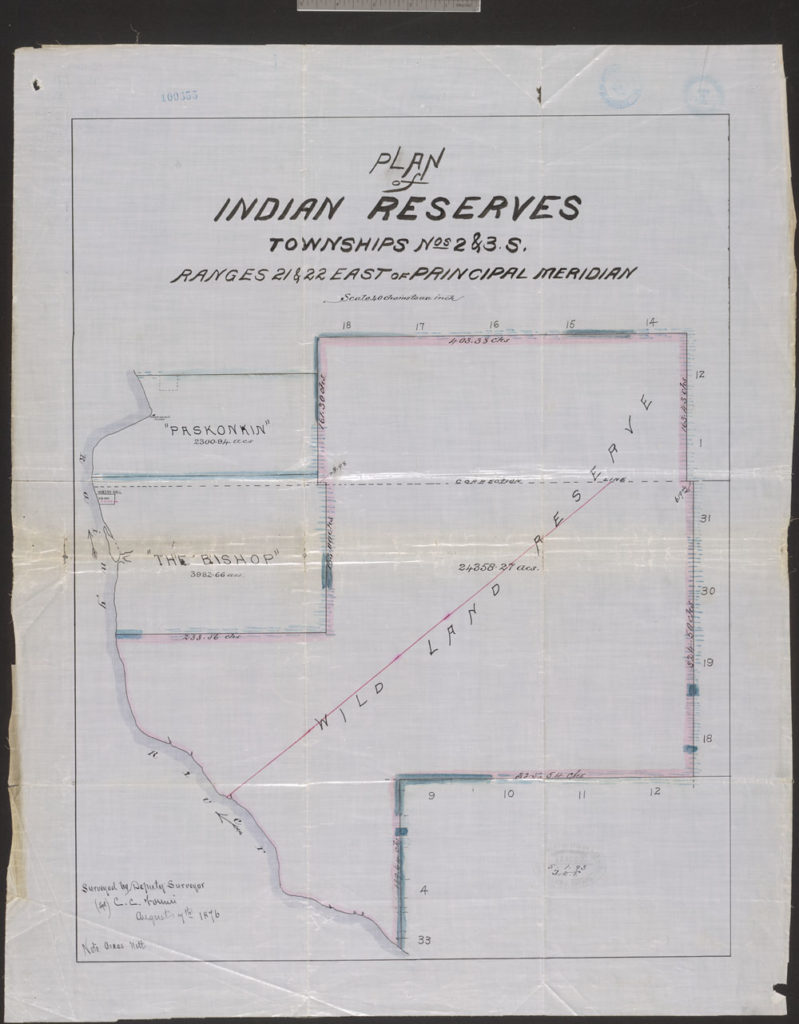

Plan of Indian reserves, townships No. 2 & No. 3, ranges 21 & 22 east of Principal Meridian. Courtesy of Library and Archives Canada

Hungry Hall No. 1 and 2, also known as Paskonkin and The Bishop, were two Ojibwe reserves situated on the Rainy River’s western mouth at the Lake of the Woods and contained 6,280 acres. Like Long Sault, Manitou Rapids and Little Forks, the Hungry Hall reserves came into existence in 1873 under Treaty 3 or the Manidoo Mazina’igan (“Spirit Paper” or “Sacred Document”). The Ojibwe negotiated the Treaty as an agreement to share their land and waterways with the Crown, yet the Canadian government continually disregarded such notions and instead used the Treaty as a further pretext to appropriate Ojibwe territory and restrict Ojibwe communities to Indian Reserves, all the while expanding white settlement in the region and enlarging large scale resource exploitation.

Two Ojibwe bands made up the Hungry Hall reserves, with a combined population of around 60 people in the 1890s. The majority of these people worked in the lumber and saw mills near the reserve, although the Hungry Hall Ojibwe also continued more traditional practices of hunting and fishing. As the reserve was just across the river from the United States, many Hungry Hall Ojibwe traveled back and forth between Canada and the US.

At one point there was a school house at Hungry Hall but it was closed due to a lack of students. With a few exceptions, such as Joseph McLeod, the Christian Ojibwe man from Hungry Hall whom Du Vernet met, the Hungry Hall Ojibwe refused Christianity. Indeed, the Church Missionary Society considered the Hungry Hall mission to be a failure, especially in comparison to Long Sault.

In 1914 and 1915 the Canadian government closed the Hungry Hall Reserves, along with the other Rainy River reserves at Long Sault and Little Forks. The government forced the Hungry Hall Ojibwe to leave their homes and settle at Manitou Rapids, where the government amalgamated all the Rainy River reserves into one single reserve.

Today, the Rainy River Ojibwe are in a long process of buying back their land. In 2005, the Rainy River First Nations and the Canadian government agreed to a $71 million settlement in recognition of the illegal amalgamation of 1914. Following a court order in February 2017, the governments of Ontario and Canada, together with the Rainy River First Nations, announced that approximately 6,000 hectares of land would be returned to the Rainy River First Nations.

Source