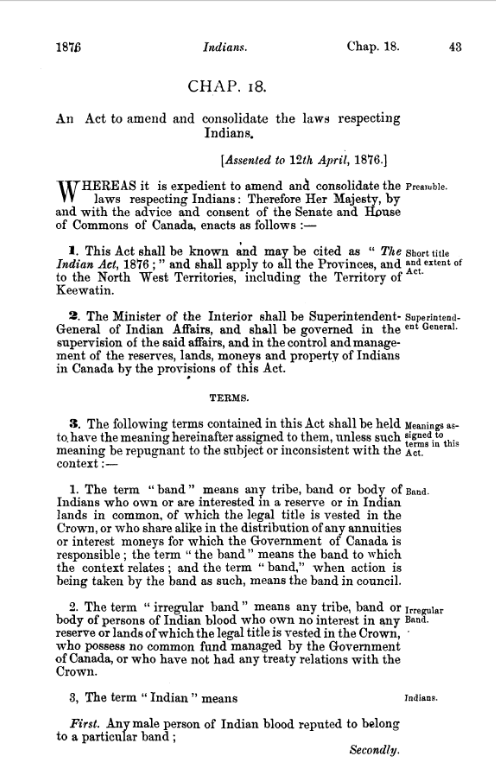

Indian Act

The power of Indian Agents and the introduction of the paternalistic Indian Act was, in the eyes of many Indigenous nations, a direct contravention of earlier treaties: where treaties were agreements between nations, the Indian Act was imposed, with no Indigenous input. Although the Act was ostensibly meant to protect Indigenous people and their traditions, it was actually designed to assimilate them.

In 1920, the Deputy-Superintendent of Indian Affairs, Duncan Campbell Scott put it this way: “Our object is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic, and there is no Indian question, and no Indian department.” Under the original Indian Act, Indigenous women lost their status and any accompanying rights if they married a non-status man, and all Indigenous people were considered “legal minors.” This meant that they could not vote, and if they lived off reserve for more than five years or obtained a higher education, their status would be taken away.

Later revisions to the Indian Act banned the practice of or participation in any traditional ceremonies such as the Sun Dance or potlatch, and made children’s attendance at residential schools compulsory. In these revisions, the Indian Act’s assimilatory and even exterminatory goals were very clear.

Today, the Indian Act remains a very controversial piece of legislation. Although Indigenous people are now legally allowed to vote, ceremonies are no longer illegal, residential schools have been abolished and apologized for, and women no longer lose status by marrying non-status people, the Act still controls who is “an Indian” through newer status requirements, and is still the main legal document acknowledging the difference between Indigenous people and settlers. For decades, many have called for its abolition, but the Act remains the primary piece of Canadian legislation that recognizes that the federal government has a unique relationship and set of obligations to Indigenous communities in the territory now called Canada.