On the Term “Indian”

“Indian”

Du Vernet constantly refers to the Ojibwe peoples he encounters as “Indians” – his use of the word reflects the language and concepts of his day. Though the category of “Indian” was a legal designation in Canada because of the “Indian Act,” as a name for Indigenous people it originated in a profound error. As the story goes, when Christopher Columbus arrived in the Americas in 1492 he believed he had arrived in India – and therefore called the peoples he encountered Indians.

The Trouble with Terminologies

Use of the term “Indian” to refer to Indigenous Peoples in North America has largely been replaced by other designations, such as Aboriginal, First Nations, or Indigenous. Thomas King explains the trouble with universal designations for Native Peoples in the following passage:

“Indians became Amerindians and Aboriginals and Indigenous People and American Indians. Lately, Indians have become First Nations in Canada and Native Americans in the United States, but the fact of the matter is that there has never been a good collective noun because there never was a collective to begin with.” (xii-xiii.)

King points out the inadequacy of grouping together a variety of different groups of peoples when they each have their own unique histories, languages, politics, social arrangements and cultures. Most First Nations prefer to be called by their own particular name in their own language. The Rainy River First Nations use both the word Ojibwe as a specific, local term, and Anishinaabeg as a wider category to describe themselves. These particular designations more accurately capture the cultures and histories of a people.

Contemporary Contexts

Universal designations obscure difference. However, collective designations enable individuals and groups to mount a collective voice of resistance against colonial powers and processes. For example, the category “Indigenous” points to the internationalization of Indigenous politics and a growing recognition of Indigenous rights worldwide.

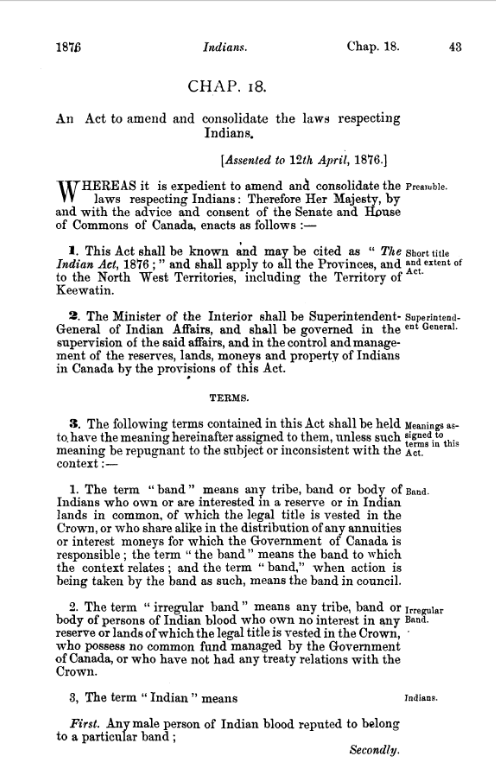

Despite the problematic nature of the word, “Indian” is still a legal category. In Canada, for example, the Indian Act of 1876 gave the federal government jurisdiction over and the right to establish the criteria for who would be considered Indian, who could claim rights, vote in band councils, and so on. The Indian Act has gone through several amendments since 1876, but it is still an active law that governs the relationship between the Canadian government and those whom it considers status Indians. “Indian” therefore remains a significant and contested legal identity for Indigenous Peoples.

Sources

King, Thomas. The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America. Toronto: Doubleday Canada, 2013.

UN General Assembly. “United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.” March 2008. View online.

Crey, Karin, and Hanson, Erin. Indigenous Foundation. “Indian Status.” View online.

National Aboriginal Health Association. “Terminology.”