This is Document #3 for The Impact of Treaties: Treaty 3 Throughout Time Lesson Plan. View the student resource page here.

Document 3: “Treaty 3: Spirit and Intent” by Keith Garrett

NOTE

This is an essay written by a student at the University of Toronto. This student used multiple sources in this essay to write about Treaty 3; therefore it is a secondary source.

Treaty 3: Spirit and Intent

by Keith Garrett

Keith is a double major in economics and history at the University of Toronto. During his undergrad he has worked on research projects with professors in the Departments of English, History, and the Study of Religion. He is also the Co-Editor of the undergraduate History and Philosophy of Science journal. Keith is currently writing a thesis on Anishinaabe understandings of Treaty 3.

The Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island (North America) made treaties with one another, both before and after the arrival of Europeans on the continent. Following contact, Indigenous peoples extended their treaty-making practices to include European nations. Both peoples made these treaties in the spirit of peace, reciprocity and friendship. Indigenous peoples continued to hold these principles into the nineteenth century. Yet European newcomers, as they grew into settler states, increasingly used treaties as a means to acquire Indigenous territory.

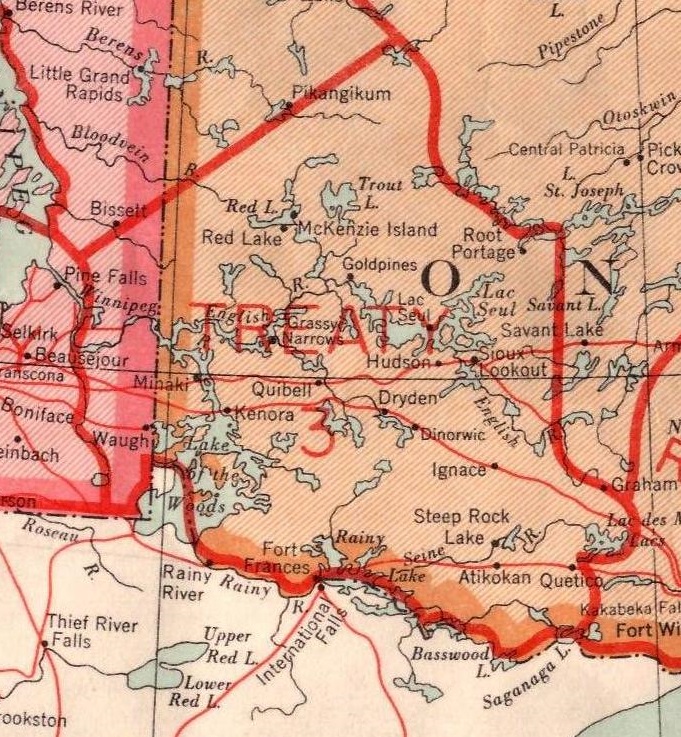

Following Confederation, Canada and the Crown negotiated eleven treaties—collectively known as the numbered treaties—with the Indigenous peoples of northwestern North America. The Anishinaabeg and the Crown produced the third of these treaties, Treaty 3, in 1873. The treaty covered a vast tract of land and water in what is now northwestern Ontario and southeastern Manitoba. The southern portion of the treaty includes the Rainy River and Lake of the Woods––the area Du Vernet recorded visiting in his diary. The Anishinaabeg negotiated Treaty 3 as a sacred covenant with Canada and the Crown, binding the two nations in peace and friendship. The Anishinaabeg agreed to share their territory with Euro-Canadians in exchange for promises of mutual respect and support. Yet Canada called the treaty a “land surrender” and argued that the treaty gave it ownership over Anishinaabe territory.

In the Anishinaabe worldview, land cannot be owned or surrendered. Instead, the Creator made the land and gave it to the Anishinaabeg to take care of. Long before Treaty 3, the Anishinaabeg understood themselves as the custodians of the land, and only permitted Euro-Canadians the right to travel through their territory. Yet Anishinaabe leaders were willing to let the Crown negotiate greater access to their territory through a treaty. Canada’s interest in Anishinaabe territory grew following Confederation in 1867. The newly formed Dominion of Canada sought to build the transcontinental railroad through Anishinaabe land and hoped to settle Euro-Canadians in the region’s fertile areas. Yet Canadian administrators realized the Anishinaabeg would not permit settlement and significant alteration to their territory without a formal understanding––that is to say, a treaty.

After several earlier attempts, representatives of the Crown met with the Anishinaabeg in September of 1873 on the rocky shores of the Lake of the Woods. Indian Commissioners Simon Dawson, J.A.N. Provencher and Alexander Morris, the Lieutenant governor of the Northwest territories and Manitoba, negotiated on behalf of the Crown; the Anishinaabeg, in accordance with tradition, negotiated collectively through councils, but were represented by chiefs Powawassin from the North-West Angle, and Mawdeopanis, from Long Sault. After several days of negotiation, an agreement was reached on the third of October. The Anishinaabeg agreed to share their territory and its resources with the Crown, but they did not agree to give up control either over themselves or their territories. The land was still theirs, and they were only letting the Crown share in some of its benefits. In exchange, the Euro-Canadian negotiators promised the Anishinaabeg support for agriculture, protection for their hunting and fishing activities, allocated land to be for the exclusive use of the Anishinaabeg (called “reserves” by Euro-Canadians), monetary payments, and other forms of support, all within a lasting relationship of goodwill and mutual obligations. The Anishinaabeg finalized the treaty with the smoking of the pipe, ceremonial dances, and gift exchanges. In their eyes, it was a sacred event, and in Anishinaabemowin Treaty 3 is called the Manido Mazina’igan (the Sacred Document or Paper).

This agreement was reached verbally between Anishinaabe and Canadian negotiators. Yet the treaty text that the Canadians drafted and both sides signed did not reflect this understanding. Instead, it falsely claimed that the Anishinaabeg agreed to “cede, release, and surrender” their territory and communities to the Crown. Following the treaty’s signing, federal and provincial governments ignored oral promises and rigidly followed the treaty text. Both levels of governments waged a campaign of repression and dispossession against the Anishinaabeg, unilaterally taking Anishinaabe lands and violating treaty rights. In 1876, the Federal government passed the Indian Act, outlawing Anishinaabe ceremonies and spiritual practices, and in 1888 the St. Catharine’s Milling Case “gave” Ontario legal ownership of Anishinaabe reserves.

Today, the Anishinaabeg continue to protest treaty violations, with many First Nations taking their treaty claims to court.

Du Vernet thus found himself on Treaty 3 land in a time of intensifying colonial oppression. The extent to which he understood the treaty’s history is uncertain. He never directly references it, but he was certainly aware of it––he refers to Treaty money and Treaty Indians in his diary. More tellingly, during a morning church service at Long Sault, Du Vernet describes the communion ceremony as a “treaty covenant.” Du Vernet later elaborated on the idea in a missionary periodical: “knowing that all the Indians were familiar with the thought of a treaty, I endeavored to fix in their minds the idea of a Covenant Feast.” By suggesting that the bread and wine of Communion were akin to the treaties signed between the Queen and the Anishinaabeg, Du Vernet implied that a promise with the Queen was akin to a promise to Christ. As the Anishinaabe understand Treaty 3 as sacred and linked to the Creator, Du Vernet’s comments were actually quite fitting.

At the time of Du Vernet’s visit to Treaty 3, Anishinaabe people across the region were petitioning the government to uphold its treaty obligations. Today, the Anishinaabeg continue to protest treaty violations, with many First Nations taking their treaty claims to court. In 2005, the Rainy River First Nations and the Canadian government agreed to a $71 million land claim settlement that identified land for future reserve creation. Following a court order in February 2017, the governments of Ontario and Canada, together with the Rainy River First Nations, announced the creation of some 6,000 hectares of reserve land.

Further reading

Krasowski, Sheldon Kirk Regina. “Mediating the Numbered Treaties: Eyewitness Accounts of Treaties Between the Crown and Indigenous Peoples, 1871-1876.” PhD diss., University of Regina, 2011. View online.

Luby, Brittany. “‘The Department is Going Back on these Promises’: An Examination of Anishinaabe and Crown Understandings of Treaty.” Master’s thesis, University of British Columbia, 2011. View online.

Mainville, Sara J. “Manidoo Mazina’Igan: An Anishinaabe Perspective of Treaty 3.” Order No. MR27478, University of Toronto (Canada), 2007. View online.

Manitoo Mazina’igan: An Anishinaabe Legal Analysis of Treaty No. 3.” Master’s thesis, The University of Manitoba, 2016.