by Nancy Xue

Nancy finished her Bachelor of Arts in Political Science and Environmental Studies in 2017. During her undergrad she was co-president of the University of Toronto Environmental Action, a club that seeks to promote awareness of environmental injustices, while seeking to engage students in direct advocacy. She is currently traveling after working as a tour guide at Vimy Ridge and will return to school in the fall to study law at the University of Victoria.

Water and Du Vernet’s Diary

Du Vernet’s diary is filled with rich descriptions of the Rainy River and the Lake of the Woods. The water is described as “beautiful” and it is something that still “lives in [his] memory.” Whether he’s giving picturesque descriptions of the lake or simply mentioning the canoe he used to cross the water, Du Vernet references water on nearly every page of his diary. From his references alone, we get the sense that rivers and lakes loomed large in the lives of Ojibwe people around the Rainy River. In fact, Du Vernet’s diary may understate the importance of water to Ojibwe people in the region. Beyond its beauty and ubiquity in their everyday lives, water in the Anishinaabe worldview is a fundamental life-giving force. It is the lifeblood of the earth.

Because it is something practically and spiritually important to people around the Rainy River, we may get a better understanding of the broader societal and environmental changes that have taken place since Du Vernet’s visit if we track changes in the local Indigenous and non-Indigenous relationships to the water.

Fast Facts on the Rainy River

The Rainy River flows into the Lake of the Woods and together, the basin covers 69 x 740 km2. The river is mostly flat and slow moving. However, Du Vernet spends a lot of time around the harsher, more rapid parts of the river known as the Long Sault and Manitou Rapids. In Ojibwe cultures the Great Spirit, who is the Creator of all things and the Giver of Life, is said to live in the Manitou Rapids.

Governing A Dividing Line

Today 59% of the total basin is Canadian territory in Manitoba or Ontario and 41% of the basin is in Minnesota. Rainy River has acted as a border between Canada and the US since 1783, so the river was already boundary water by the time Du Vernet visited. He writes about the river as a border when he brings up a fishing station on the “American side” and comments that he saw US flags flying on the Canadian side of the river. However, there would not be an official project to survey and mark the boundary between Ontario and Minnesota until the Treaty of 1908. Although the project did not bring major changes to the pre-existing boundaries, it was not until 1931 that the official borderlines for the region were publically released. So, it is interesting that Du Vernet refers to the river as a dividing line because as he was writing, there were still conflicts over where exactly the “American side” started.

Cooperation between the two governments and management of the boundary water has grown since 1898. The International Joint Commission (IJC) was established under the Boundary Waters Treaty of 1909. Today, it regulates shared water uses and investigates transboundary issues. Many other international organizations have also been created to help take a cooperative approach to managing the Rainy River and Lake of the Woods boundary waters. In a way, the story of the Rainy River as boundary water mirrors elements of Canadian-US relations; the countries have gone from expanding nations butting heads over territory into the mostly cooperative countries that they are today.

The Hidden Consensus: Sovereignty for Some

Yet, the story of the border-making process leaves out the Indigenous peoples in the region. These communities had been interacting with the Rainy River for much longer than settlers from the two nation-states had been. In recent years there have been more efforts to consider Indigenous voices. Today, the IJC often includes Indigenous peoples in the decision-making process through the duty to consult. Still, the Indigenous peoples are not the ultimate deciders. The IJC continues to stand on the premise that it is not a multinational governance mechanism, but a binational one. First Nations and other Indigenous groups can only make “legitimate” requests through the IJC if they have approval from the Canadian or US government.

On the surface, the transition of the Rainy River from a contested border to a site of consensus and joint governance between the US and Canada tells the story of accommodation. If you examine the arrangement more closely though, it is evident that these seemingly neutral borders and institutions are anything but neutral. They are premised on the domination of Indigenous peoples and the refusal to incorporate them as relevant, autonomous nations within an international issue that directly concerns them.

100 Years of Industrial Activity

In 1884, dams began to appear along the Rainy River. These dams were used to help sawmill operations and to produce hydropower, yet they often flooded out reserve croplands and destroyed agriculture production. So many crops were destroyed that it caused many Ojibwe to starve in the winter. In fact, the IJC was initially created to help establish regulatory measures to prevent flooding in the district.

Around this time, sawmills were also established at Lake of the Woods, Rat Portage, and Fort Frances. It was a common sight to see thousands of tree trunks floating downstream – these were called log drives. Large dams were built along the river to stop the flow of logs and Du Vernet himself mentions passing a “large boom” that sorted logs as they floated away.

Just as the need to log for the railway faded, the pulp and paper industry rose up. The Fort Frances pulp and paper mill first went into production in 1914. The industry was a strong economic force in the region for almost a hundred years before the pulp and paper mill at Fort Frances has finally closed. Mineral extraction also increased throughout the district in the 1890s, though most mines closed by the 1940s. In recent years, however, there has been a resurgence of interest in mining the area. All of the industrial activities have degraded the water quality in the region.

The Rainy River and its tributaries also face excessive algae growth. This algae growth is due to changes in agriculture, irrigation, and industrial pressure, all of which lead to phosphorus runoff. The phosphorus helps bacteria bloom on the water surface. This blocks sunlight from reaching deeper parts of the lake and alters the oxygen balance of the water, which causes many aquatic plants and animals to die. The whole process is known as eutrophication. The bacteria itself is also harmful to humans and can cause headaches, fever, diarrhea, and irritation to skin and eyes.

Efforts are underway to improve the water. In 2015, the IJC submitted their report “A Water Quality Plan of Study for the Lake of the Woods Basin” to the Canadian and US governments. It aims to address complex water quality issues and ecological concerns. Most interestingly, the report attempts to reframe its approach to water source protection in a way that considers the interrelation between human and ecosystem health. Indigenous peoples have understood these interrelations long before settlers arrived in North America. Nevertheless, 100 years after the creation of the IJC, we are just now seeing a delayed incorporation of Indigenous perspectives on water and the environment.

Industrial Activity and its Impacts on Indigenous Life: A Case Study of Sturgeon

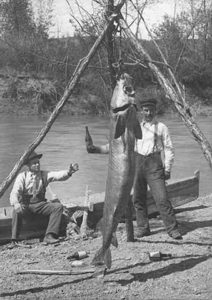

The sturgeon, known in Ojibwe as Namewag, has been central to the way of life of Ojibwe people around the Rainy River for centuries. Archaeological evidence shows sturgeon fishing along the river dates back to at least 500 B.C. Sturgeon were frequently mentioned in local myths and giant sturgeon were often associated with the spiritual power of controlling fisheries. This suggests that sturgeon had a religious significance for Ojibwe people. The Lake of the Woods used to be known as the greatest sturgeon pond in the world and the Rainy River was a major spawning ground, particularly in the Long Sault and Manitou Rapids sections. So when Du Vernet asks his “Indian” guide whether there are fish in the rapid waters, he was unaware that, at the time, those rapids were some of the best fishing grounds for sturgeon.

All of this is to say that sturgeon and fishing used to be an extremely important part of life for Ojibwe people in the Rainy River region. However, today the sturgeon population has significantly declined since the turn of the 19th century and this is mostly due to the arrival of non-Indigenous commercial sturgeon fishing. Fur traders relied on the sturgeon catch from Indigenous people for their own consumption and the Hudson Bay Company harvested substantial amounts of sturgeon for isinglass, a by-product of sturgeon used to make glues, beers, and wines. Still, the sturgeon population was not under threat until the mid-1880s. In fact, Treaty 3 heavily emphasizes the First Nations peoples’ fishing rights and this point was not seen as contentious when the agreement was struck in 1873. Yet by 1888, the Canadian federal government was facing enormous pressure from preservationists and First Nations to stop industrial fishing. The government agreed to their demands and stopped non-native industrial fishing on the Canadian side. However, they did nothing to stop the industry on the American side. Then, just a few short years later in 1892, the government reversed their policy and once again allowed unregulated commercial fishing. When Du Vernet visited the region in 1898 he was visiting during the heyday of industrial fishing. Nine million pounds of sturgeon were caught between 1892 and 1898. These fishing practices were unsustainable and, unsurprisingly, the industry collapsed very quickly. In 1905, a fisheries biologist reported to the Canadian government, “No fishery is so easily exhausted by reckless, unrestricted fishing.”

The pollution coming from activities like paper production and mining, as well as the disturbance of water flow caused by hydro-electric projects, have also threatened the sturgeon population. So, although fishing appears in Du Vernet’s diary a couple times, this may not have been the case if he had visited a decade later.

This population collapse had significant impacts on the Rainy River First Nations. When the ethnographer Ruth Landes conducted research at the Manitou Rapids Reserve from 1932 to 1935, she found that fishing was of little importance to the people living there.

The disappearance of sturgeon is a concrete example that sheds light on the drastic cultural and lifestyle changes First Nations underwent due to the landscape changes and environmental pollution caused by settlers and settler activities.

Mercury Poisoning, Logging and Resistance

First Nation peoples in Canada continue to suffer from evolving water-related environmental issues over a century after the arrival of intensive industrial activity. One major example comes from the Grassy Narrows First Nation and the White Dog First Nation communities. They are located near Kenora, a town that used to be known as Rat Portage when Du Vernet was writing. In 1962, a nearby paper mill began dumping its untreated mercury waste into the communities’ water source. High mercury levels were detected in the water in 1969 and in 1970, when the Ontario government finally ordered the company to stop its mercury dumping. By this time over 9000 kg of mercury was dumped into the river.

For years the Ontario government refused to help the victims because they claimed the mercury would only affect the environment and it would not harm human health. The government finally began negotiating a compensation package in 1978. Still, the Ontario government refused to clean up the river. To this day it insists there must be more studies done on the feasibility of a clean-up even though it has been demonstrated that reducing the mercury levels is doable and safe.

Meanwhile, mercury poisoning continues to hurt the people living in the community today. One published study shows that 79% of people tested in the two communities in 2002 and 2004 still suffer from severe mercury poisoning, with symptoms including tremors, muscle loss, and death. Furthermore, the mercury poisoning also resulted in the social and economic breakdown of the communities. The fishing industry was forced to shut down in 1970. That same year, the unemployment rate in Grassy Narrows went from 5% to 95% and one fifth of all children aged 11-19 attempted suicide. These limitations on fishing also lead a deep sense of loss of culture and identity.

The people of Grassy Narrows have also endured industrial clear-cut logging for decades. Roughly 50% of the area is now logged. Yet, community resistance to this deforestation grew considerably in the late 1990s when extremely large portions the forest were being cleared. This encroachment on their rights, coupled with a lingering sense of wrongdoing from the mercury poisoning and the community’s growing awareness of Indigenous and treaty rights, emboldened Grassy Narrows to take action.

On December 2nd, 2002, youth from the community began the longest standing indigenous blockade in Canadian history. It still stands today. The intent was to stop logging trucks from entering the territory, but it was also a greater stand for sovereignty over their lands. Companies continued to log around the area for the first few years but the direct action continued. In 2008, the largest logging company in the area withdrew from the area due to the mounting pressure.

Over the years there have also been rallies, speaking tours, and boycotts against the Ontario government’s permissive attitude towards industrial activity on native territory and to pressure the government to clean up their water. In 2008, many Grassy Narrows members walked 1800 km from their community to the Provincial Legislature in Toronto to demand the government take action and address the lack of clean drinking water in the community. Since then, the people of Grassy Narrows have held annual rallies and marches to call attention to their situation. In 2014, a Grassy Narrows member with mercury poisoning went on hunger strike to call for the clean-up of the river. In short, Grassy Narrows remains resilient in the face of governments and corporations.

Water All Around Yet Nothing You Can Drink

Unsafe drinking water is not only an issue for the White Dog and Grassy Narrows communities. Nearly two-thirds of all Canadian reserves have been under a drinking water advisory in the past 10 years. The issue is so dire that in June 2016 Human Rights Watch released a report calling on Canada to end the First Nations water crisis.

This crisis certainly affects the Rainy River First Nations. Despite the abundance of water in the region, the Rainy River First Nations have been put on and off the drinking advisory several times in recent years. From August 2015 to February 2017 alone, three drinking water advisories were issued and rescinded. On the other side of Lake of the Woods in Manitoba, the Shoal Lake 40 First Nation community has been under the same drinking water advisory for over 20 years now.

Indigenous communities and individuals are not enduring these water issues passively.

There are many different reasons why the individual water treatment systems fail. Sometimes they fail due to agricultural runoff, sometimes there may not be pipes leading to all the houses on the reserve. The diversity of issues is part of what makes the problem so challenging. On top of this, First Nations do not receive the same legal protections for safe drinking water as Canadians living off reserves.

This makes for a situation that people like Du Vernet, who lived 100 years ago, would probably never have imagined. Water is all around, yet there is nothing you can drink.

Water Walkers and the Resilience of Communities

Indigenous communities and individuals are not enduring these water issues passively. The Grassy Narrows community and their fifteen-year-long blockade show an exceptional amount of perseverance. However, they are far from being the only story of Indigenous resistance in the face of water crises.

Josephine Mandamin is one of the two Ojibwe grandmothers who founded the Mother Earth Water Walk in 2003. She was concerned about the state of water because over her lifetime she has seen the water’s health decline and the ecosystems fail. Furthermore, in her people’s tradition, as in many Ojibwe nations’ traditions, women are the keepers of water. Thus, she took it upon herself to raise the collective consciousness of the impacts of pollution on water and the Spirit of the Water; Josephine organized a group of people to join her and walk around Lake Superior. The water walkers carried water in copper according to Anishinabe ceremonial traditions. The walk was long and took over a month to complete. Nevertheless, Josephine organized another walk the following year. These walks are now annual events and Josephine has walked over 20,000 km for water, equal to nearly half the earth’s circumference.

What is particularly inspiring about the Sacred Water Walks is how the water walkers have taken Anishinabe customs and make them into both a means and an end. By celebrating and following traditional customs of Anishinabe nations, the water walkers are honouring Anishinaabe traditions. At the same time, this visible display of culture and customs is a way to resist the water crisis on reserves. It also serves more broadly as a means to resist colonialism and assimilation.

We are also witnessing growing alliances between Indigenous and non-Indigenous groups as a strategy for resistance. In 2009, non-Indigenous residents of Tiny Township, Ontario and surrounding communities joined forces with the Beausoleil First Nations to protest a proposed landfill on land called Site 41. Site 41 lies above the Alliston aquifer, which has been tested and found to contain some of the purest water in the world. Mohawk Elder Danny Beaton of Six Nations, Turtle Clan, and long-time Site 41 opponent Stephen Ogden took part in a peaceful walk from Site 41 to Queen’s Park. That summer, supporters set up a resistance camp near the planned landfill site. For one hundred days, the camp was a beautiful collage of teepees and tents. These collaborative protest efforts lead to success, as the landfill plans were revoked.

More recently, there have been larger Pan-Indigenous movements across North America like Idle No More and the Standing Rock resistance. Like Site 41, these movements have linked up with other causes, most prominently the environmental movement. This is not to say that Indigenous voices are being subsumed into existing leftist frameworks. Rather, alliance building bolsters complementary causes while keeping the combined voices distinct.

One of the major rallying points in these Pan-Indigenous movements is the protection of water, both on and off reserves. In fact, a popular rallying cry is “Water is Life.” So, after decades of industrial activity, after the decimation of the sturgeon and other fish populations, and after the significant degradation of the water quality, the spiritual significance of water for many Indigenous nations carries on today.

Conclusion

This closer examination of water as it figures in Du Vernet’s diary and in peoples’ shifting interactions with the Rainy River has revealed broader social, political, and economic realities about the region from Du Vernet’s time until today. The history of this water reveals changing Canadian-US foreign relations and the shared premise of excluding Indigenous peoples that both nations work from. This examination also reveals the booms and busts of industrial activities in Canada, its effects on Indigenous life, and the prominent contemporary environmental issues that these activities eventually lead to.

The degradation of water quality over the years should be seen as a particular affront to Indigenous peoples, given their spiritual understandings of water. Yet, the persistent resistance and contemporary understanding of the sacred importance of water tells us that neither missionaries like Du Vernet, nor industrial activities going on in the region, nor modernity could successfully erase the cultures and spiritualities of the First Nations. Their stories continue today.

Bibliography

Amarasingam, Amarnath and Morgan, Sarah. “No landfills! Tiny Township celebrates anniversary of Site 41 moratorium,” Rabble, Oct 17, 2014. View online.

“Canada violates human right to safe water, says report by international watchdog,” CBC, June 11, 2016. View online.

Deerchild, Rosanna. “Water walkers: Indigenous women draw on tradition to raise environmental awareness,” CBC Radio, Sept 5, 2015, View online.

Du Vernet, Frederick H. “Diary of a Missionary Tour” (Toronto, 1898), M81-41, Anglican, Church of Canada Archives.

“First Nations and Inuit Advisory Reports,” WaterToday, Feb 10, 2017. View online.

“Grassy Narrows 12-year blockade against clear cutting wins award,” CBC, May 24, 2015. View Online.

Holzkamm, Tim E. and Lytwyn. Victor P. and Waisberg, Leo G. “Raiy River Sturgeon: An Ojibway Resource in the Fur Trade Economy,” The Canadian Geographer 32 no. 3 (1988).

Ireland, Nicole. “Steve Fobister ends hunger strike,” CBC, July 30, 2014. View online.

Keenan, Greg and Parkinson, David and Jang, Brent. “Paper trail: The decline of Canada’s forestry industry,” The Globe and Mail, Dec 5, 2014. View online.

Kelly Crowe, “Grassy Narrows” Why is Japan still studying mercury poisoning when Canada isn’t?” CBC, September 2, 2014. View online

Lass, William E. Minnesota’s Boundaries with Canada: Its Evolution Since 1783 (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1980).

McGrath, John Michael. “How the waters of Grassy Narrows were poisoned,” TVO, September 23, 2016. View online.

McGregor, Deborah. “Honouring All Relations: An Annishnabe Perspective on Environmental Justice” in J. Agyeman, P. Cole, R. Haluza-Delay, P. O’Riley (eds.) Speaking for Ourselves: Environmental Justice in Canada, Vancouver: UBC Press, 2009.

Norman, Emma S. Governing Transboundary Waters: Canada, the United States, and Indigenous Communities (New York: Routledge, 2015).

Oblak, Jacqueline A. “Water and Health in Lake of the Woods and Rainy River Basins” for Health Professionals Task Force International Joint Commission, June 2009. View online.

Paikin, Steve and Day, Isadore and Picotte, France. “Indigenous Perspectives on the Great Lakes,” TVO, Oct 7, 2016. View online.

Poisson, Jayme and Brusser, David. “Province ignored minister’s 1984 recommendation to clean up mercury in river near Grassy Narrows: Star Investigation,” The Star, July 4, 2016. View online.

Thompson, Jon. “NDP Leader commits to building Freedom Road to Shoal Lake 40,” Thunder Bay News, July 26, 2015. View online.

“2003, Lake Superior,” Mother Earth Water Walk. View online.