Click on the “play” button to hear the diary episode read aloud, and click on the green tab 1 to learn more about a word or phrase.

Find Du Vernet on a map.

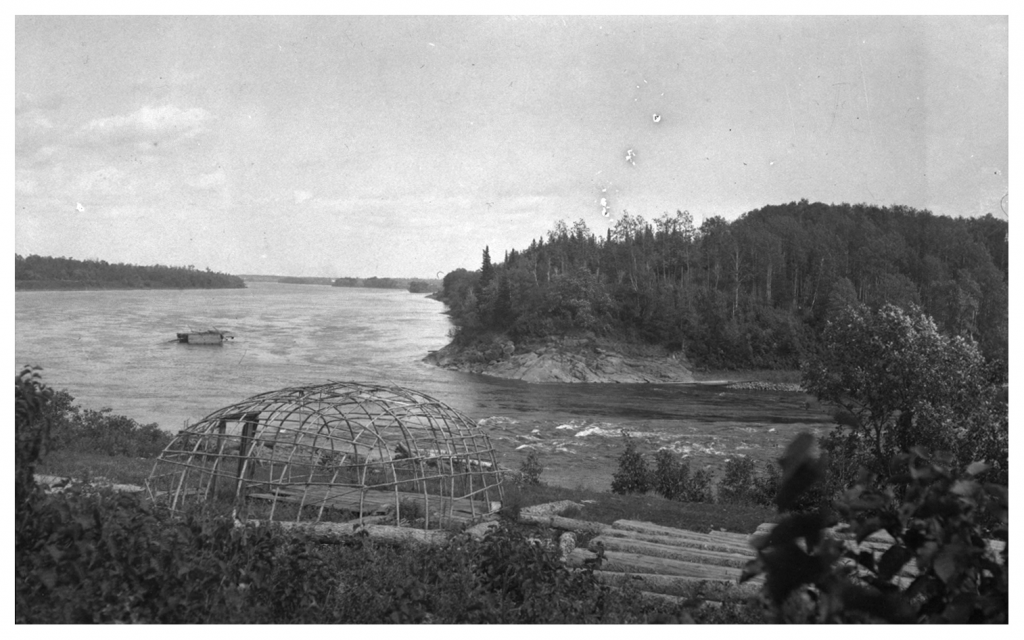

On Monday morning, July 18, I took a picture of the

Johnston family 2 and Mr. and Mrs. Wood 3 near the Church, as the Woods were returning home.

In the afternoon I took a most interesting walk through the reserve 4 along the River bank.

First, we visited “grandfather 5 ” and grandmother, who were in their house. They showed us a long Indian 6 pipe and some very fine bead work, including a Cloak, Cloth, Trousers, and two Sashes. Once, to show his hatred of the Sioux 7 tribe Grandfather bit a piece of the flesh from [something].

The old woman 8 is greatly opposed to Christianity 9 .

Going on we passed three graves 10 which I hope to photograph. They are surrounded by a fence. A chair stands inside, and the three graves are covered with a pointed roof. A flag staff with a white flag at the top and another half way up stands at the foot of each grave. The bodies are put into the grave in a sitting posture, then branches are put across them and about a foot of earth placed over this. Then a little house is built over this, sides and a roof, and there is always a little door and a shelf below this, and a spirit is supposed to come in and out of this door to get what is placed there on the shelf and on the ground around the grave.

I have seen knives, forks, cups, tumblers, and a tin rattle filled with shot, which the mourner rattles when he sits waiting at the grave. Ribbons were fastened round the door of one grave, and wild berries were often placed there. Women coming home from the woods after picking berries will often place a few on this shelf. On one shelf I saw a 10¢ piece. I inquired if that would be allowed to stay, “Oh Yes” Mr. Johnston said. Though of course in time it disappears, but then they think 11 the departed one has come out of the grave and taken it.

We visited the School, a fine building like that of Little Forks 12 . (The double windows are still on.) The teacher lives in a little house nearby with a beautiful view of the rapids. Mr. Bagshaw 13 put up the fence. A journey through the woods, filled with mosquitoes and “bull dogs,” brought us out on the bank once more.

We heard the tom-tom 14 sounding and went to see. (Some young Indians saw us coming). In a large log house we saw the tom-tom. Although the place was now deserted, it was where the dance of Sunday evening was held. “The long tent” or medicine tent 15 is the name they give such a place.

The young Indians looked ashamed 16 when they saw us going in. Round the house were cedar tips 17 covered with matting. On this they sit and dance. A little further on we entered a regular tepee. Tepee is the Sioux word, wigwam 18 is the Ojibwa word. In this tent we saw Chief Black Bird 19 , son of the old Chief 20 , and McGuire, an Indian pilot 21 with a sailor’s beaked cap and a hard face, who is addicted to drink, and Thomas Bunyan 22 smoking on his long tomahawk pipe. (Quite a picture)

There were also two other Indians, playing cards . These were all seated on matting placed on cedar twigs. The tepee was made of poles covered with birchbark except on top a large open space. We talked to these men. I said I had come a long way to see them and was glad that they had such a fine reserve and hoped that they would have God’s blessing etc. They all laughed 23 when I slapped Mr. Johnston on the shoulder and said I trusted my life to him while coming down the rapids.

Outside under a “shade tent” was Chief Black Bird’s wife, in decline. She looked ill, but as she had been going through the medicine tent (or long tent), she declared she felt better.

Close to her was a large red cross with some marks on it, and near by was another large tent or canvas tepee, which belonged to American Indians 24 who had come over to gamble. We shook hands with many of them, and John Cochrane 25 was amongst them. They were playing cards.

In some of the tents Mr. Johnston happened to mention that he was going on to McGuire 26 ’s. As we walked on round one of the tents by the river, an Indian boy passed us running at full speed, and he did not stop when spoken to. He was no doubt sent to warn the people at the upper end of the reserve that we were coming. There was no doubt gambling going on there.

We passed two prehistoric Indian mounds 27 . The Indians will not allow them to be opened. Near here were some more graves. One was only 2 weeks old.